Danny Dieleman: One loan, two different capital requirements

This column was originally written in Dutch. This is an English translation.

By Danny Dieleman, Wholesale Banking Director Capital Treasury, ING

Private credit is growing rapidly, and banks are increasingly facing competition from insurers and alternative lenders. It is striking that banks and insurers have different capital requirements for the same loan. This raises the question of how this is possible. Is this a flaw in the system, or is it actually a clever design?

Banks and insurers are both players in the financial system, but their core activities are completely different.

Banks collect money from savers and lend it to businesses and households. Their customers can withdraw their savings immediately, while loans have long terms and cannot be called in by the bank in the meantime. This exposes banks to liquidity risk. If many customers want to withdraw their money at the same time, a bank can run into problems. We saw this recently with the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank.

Insurers, on the other hand, operate primarily on the basis of long-term commitments. They receive premiums and often only pay out claims or life insurance benefits years later. Their commitments are stable and cannot simply be “called in”. An insurer is therefore never affected by a bank run.

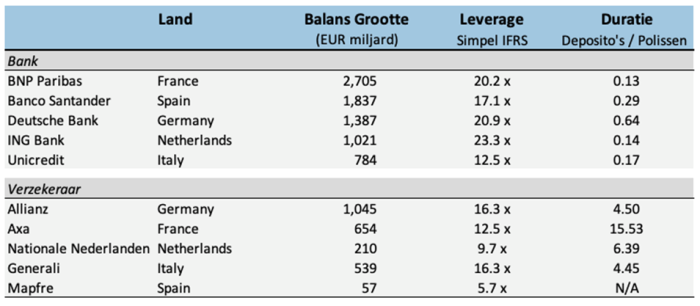

These differences mean that the balance sheets of banks and insurers have different compositions. Figure 1 illustrates a number of these differences for the largest European banks and insurers, based on the 2024 annual reports.

Figure 1

The following points stand out in the table:

- Banks are many times larger than insurers

- Banks have much greater leverage

- The duration of liabilities is many times shorter for banks than for insurers

Different rules apply to different risks

Due to their different roles in the economy and the different compositions of their balance sheets, banks and insurers are subject to different supervisory rules.

For banks in Europe, the CRR regulations (based on Basel III) apply. Credit risk mainly concerns the chance that a customer will not repay. The capital requirement depends on the type of customer or the quality of the underlying collateral.

For insurers, Solvency II applies. Under this regulation, a loan is valued at market value and capital requirements apply to both credit risk and fluctuations in the valuation of assets. The term of the loan is very important here. The longer the loan, the greater the volatility in value.

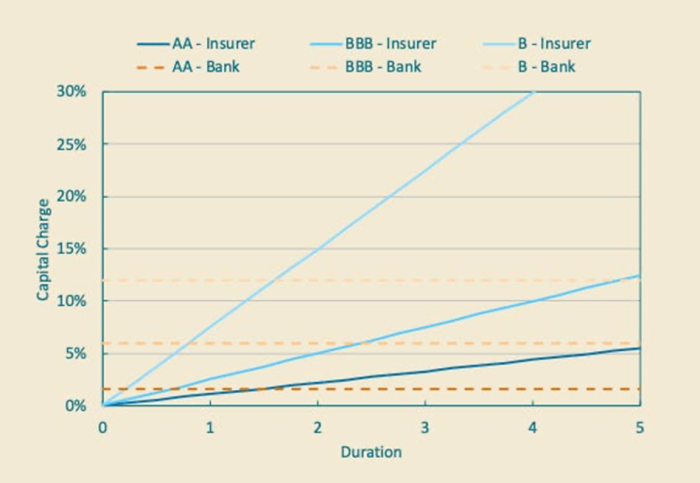

Figure 2 shows the capital requirements for banks and insurers for loans with an external rating based on the standard formulas in the CRR and Solvency II (i.e. not based on internal models). This clearly shows that the capital requirements for banks and insurers are not the same. For banks, the capital requirements are independent of the term of the loan, while for insurers, the capital requirements increase with the term.

Figure 2

This seems to contradict the long maturity of insurers' liabilities. However, what is not yet taken into account here are the diversification benefits that insurers enjoy. In addition, Solvency II mitigates spread risk, because not all spread risks are relevant.

Spread makes all the difference

Insurers are allowed to take capital advantages into account because not all risks will occur at the same time. The legislator even prescribes formulas for calculating these diversification benefits. This can significantly reduce the total capital requirement, sometimes by as much as 30% to 40%.

For banks, on the other hand, diversification is only taken into account to a very limited extent. Under the standard rules, individual risk figures are simply added together.

The result: for loans with a maturity of up to three to four years, an insurer may actually have more room on its balance sheet than a bank. For very long-term loans, the capital requirement increases again.

Arbitrage or smart architecture?

It is sometimes thought that parties simply take advantage of differences in rules to save capital – regulatory arbitrage – but that is too simplistic.

At the loan level, there is no arbitrage: if a loan is not repaid, both banks and insurers will suffer the same economic loss. This is only reflected in different accounting methods. For banks, the losses are reflected in provisions, while for insurers they are reflected in a reduction in the market value of the loan.

The capital held by banks and insurers is intended as a buffer for losses at portfolio level. These buffers protect savers and policyholders and must therefore be appropriate to the credit and investment activities of the institutions, as well as to the maturities of the liabilities.

It is therefore entirely logical that there are differences in capital requirements between banks and insurers, and this is certainly not a case of arbitrage. Regulatory arbitrage does exist, but this only occurs when transactions are structured in such a way that a lower capital requirement is achieved without reducing or eliminating the risk.

What does this mean for financial markets?

The differences in capital requirements between banks and insurers create opportunities for cooperation.

- Who should be the holder of a specific loan?

- Loans with predictable cash flows are more suited to insurers, while flexible facilities are more suited to banks.

- Do banks and insurers currently have the right loans?

The current way of structuring loans may not be optimal, but a partnership between a bank and an insurer opens up more possibilities in terms of structuring.

- Smart structuring can help everyone

- Think of tranches or tailor-made maturities that match capital and liquidity needs.

- Does it fit into the investment mix?

Do illiquid loans fit within the insurer's risk appetite?

- Capacity and expertise are crucial

- Insurers must have the right knowledge to be able to assess and manage credit throughout the term of the loan. If this knowledge is not available, it will have to be outsourced to an asset manager.

Conclusion

It is not a flaw in the system that a loan on a bank's balance sheet is treated differently from a loan on an insurer's balance sheet. It is, in fact, a conscious choice in the design of our financial system. And when both parties leverage their strengths, this can lead to better financing for the real economy.

Want to read more about this topic? You can do so here: Substack-Smart-by-design-or-Flaw-in-the-Design

Disclaimer

The ideas and opinions in this article are my own and not those of my employer. I am writing this blog purely for informational purposes, because I find the subject interesting and hope to inspire others with it. It is therefore not investment advice. Always do your own research before deciding whether or not to invest in something.